Field Diaries

Playing at the intersection of ethnography, visual art and storytelling…

BlueUrban is as much about the micro-practices and politics of everyday urban life along shorelines. While seeking to create grounded, fine-grained ethnographies of coastal urbanities in a time of multiple socio-ecological crises (and transformative moments), we very much seek to create a praxis of writing in place, and not just from place.

In such contexts, the notion and boundedness of the “field” – as an interactional, experimental, and as a disruptive social field in its own right is critically scruitinised, drawing inspiration from affective, postdevelopment and decolonial perspectives. Therefore our “dispatches from the field” serve two purposes.

Firstly, this space was created to enable researchers, practitioners, and public scholars to reflec11t on our specific fieldwork positionalities, encounters and everyday ethics – whether it be on the fringes of craggy coastlines, or in the archives of national libraries whilst laying bare perplexities and themes that might otherwise have thought to be “notoriously private” or rendered insiginificant (see Golub, 2009). Taken together, these critical reflections and methods have been invaluable for teaching, as much as praxis.

Moreover, nascent approaches in auto-ethnography, non-representational ethnography (Vannini, 2014), “patchwork ethnography” (Gue1nel et al., 2020) and the “ethno-graphic” (Rumsby, 2020) for example, continue push the boundaries of experimental expression, making way for newer and more meaningful ways of sensing, understanding, storytelling, and of collaborating with diverse spaces and communities.

Secondly, this space aims at sharing oral life histories and personal narratives as expressed by participants, in ways that bring together intersectional biographies of people, infrastructures, and the more-than-human alongside contemporary understandings of socio-environmental and political change across littoral contexts.

Together, these portraits, personal reflections, auto-ethnographies and collaborative forms of storytelling are pieced together as texts, vlogs, social mapping formats, and other audio-visual artistic modalities, and aim to create an archive of everyday coastal urbanities specific to the cities explored.

We also very much welcome collaborative and guest contributions comprising writing and visual essays that are grounded in everyday encounters, fieldwork-related experiential knowledge and/or activism.

February 27, 2018

Rapti Siriwardane-de Zoysa (ZMT)

First published online in Marine Coastal Cultures

It was in May 2017 that I became stealthy seawall walker, when I finally mastered the fear of losing my footing, clamoured atop some loose concrete to gingerly tread the length of about half a mile above northern Manila´s cinereous-grey breakwaters. Its coastal waters yawn out to the South China Sea, taking your breath away.

Drawing you into its metallic fold, what greets the eye is an almost dystopian Boschian image entailing cranes, cutterheads, booster pumps, sand spreaders, and hydraulic fills of military precision – some that crank through the night.

What meanings and sensibilities about do coastal protection agencies carry, particularly against the backdrop of Navotas´ diverse social collectives – from its harbour societies to its ship building industries and its informal fisher settlements? The very term coastal defense bears a narrow set of visions and susceptibilities of/for living with or without water.

“It’s a war against the sea” – the surging tides – suggest groups of local and foreign engineers who lend their mercenary expertise. The temporary makeshift concrete and wooden structures which they cohabit are referred to as “barracks” at times stilted and often built with the assistance of resident fishing communities. Yet these structures depict very little of the amphibious scaffolding of the informal settlements that dot the densely built coastal spaces of Navotas, that also houses its urban fisheries port.

Perhaps one cannot help but to think back on the old days of hydroelectric dam-talk, replete with its discourses on taming and reigning in the white waters of those expansive transboundary rivers, making “nature” do its work. If the 70s and 80s were flecked with the modernist rationalities of dam building, perhaps the next few decades will be shaped by the contours of giant seawalls and other coastal defense fortifications? Against the contested backdrop of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ boundary-protection methods, the terrestrial or the amphibiously-inspired, what mental models do the futures of contemporary coastlines stand to offer, particularly in spaces across Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas?

Arguably their visionary desires often entail composite contradictory imaginaries and technics representing manifold ways in which communities, particularly those comprising densely populated urban societies will be living with/out water in the decades – if not centuries – to come. What arguably appears to sit in stark contrast to one another are the polarized narratives between living amphibiously with the watery incursions (and ‘promises’) that relative sea level change, compounded by land subsidence, seem to present.

Coastlines are not only contemporary riskscapes, re-chiselled through circular narratives of ecological disaster, vulnerability, social uncertainty and precarity. They are also being increasingly although less visibly refashioned as interventionist spaces for engineering experimentation (taking for example newer island reclamation and dredging projects), and as new profit frontiers in which hybrid sciences and political acumen come together in adapting to sea level change through purely technical means.

On the other hand, the avid fervour with which coastal land acquisition and privatization projects are being rolled out across diverse neoliberal cities, from Lagos to Suva, Bonaire to Jakarta present contradictory world-making visions of waterfront living. If the post-war “coast rush” has been unfolding over the course of several decades, do the philosophies and enactments of architectural utopias and political projects such as Amphi-bios constructions and sea-steading advance particular sensibilities of idealized coastal life, and of littoral space depicting the ways in which they ought to be appropriated, legitimately used and consumed?

Yet the hard, unrelenting surface of this newly built embankment brings me back to the fixity of Navotas´ urban coastal form – and this wall-as-boundary, as I delicately side-step other passers-by who balance their way along its loose rubble. Children often scale its concrete, preferring to walk along its ragged edges. The wall in many ways presents a cracked margin in which the informal settlements of particular barangay-neighbouroods of Navotas now sit behind its bulwark, almost as if sheened in seclusion against the impending storm surges that are predicted that year.

This piece in no way presents a normative claim to state that walled-in coastal life is either positive or negative in itself. Think local context, and whose interests are being served. Yet like older narratives on renewable energy security, those of climate-induced sea level rise do produce compelling imaginaries and nomenclatures of their own, even if used to legitimate other desires: of no-retreat, building up and out, of ‘taking back’, re:claim(n)ation.

Meanwhile as larger fortifications continue to segment vast stretches of the world’s urban shorelines, these structures would continue to inexorably transform the many tangled everyday relationships between people and the sea.

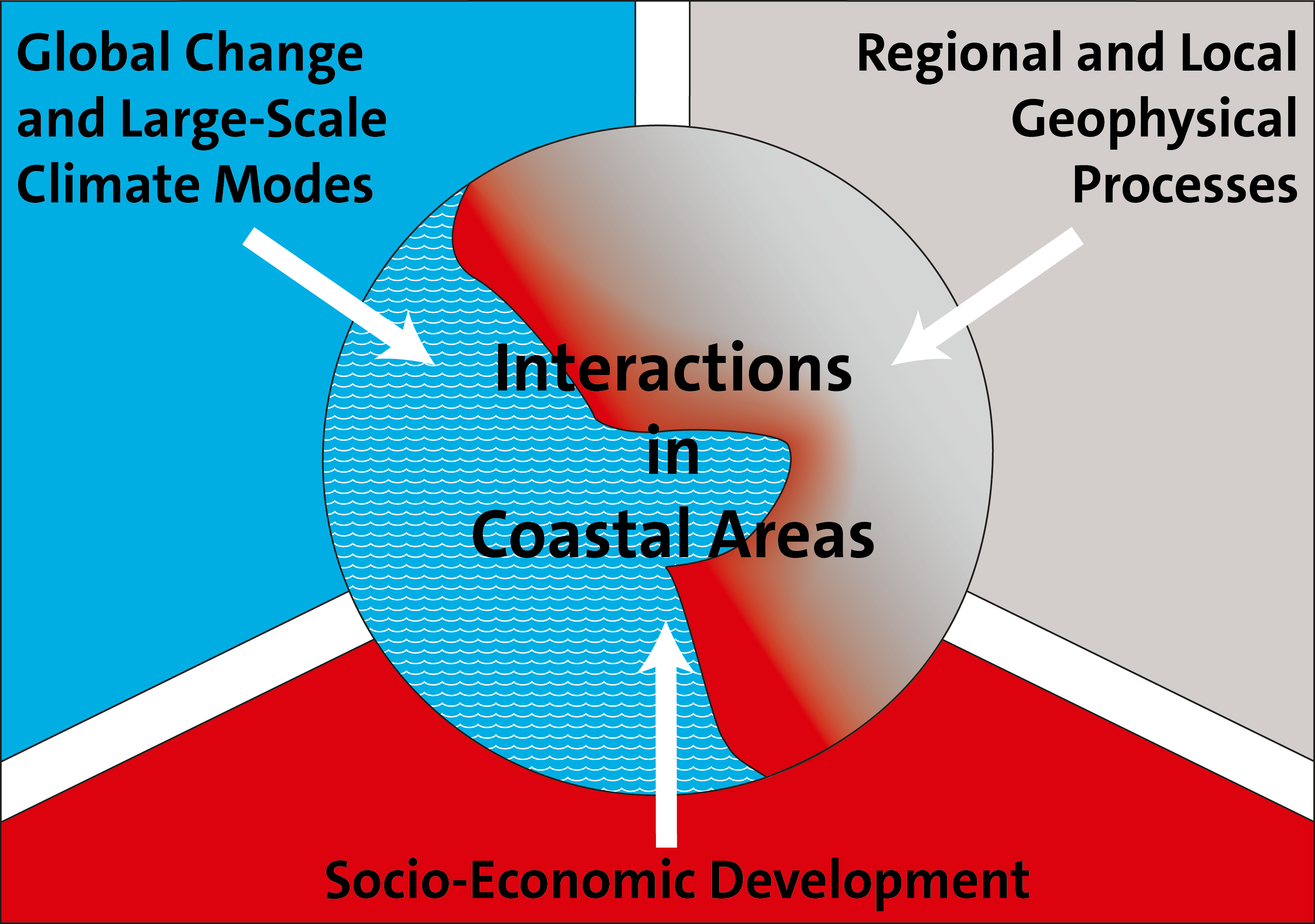

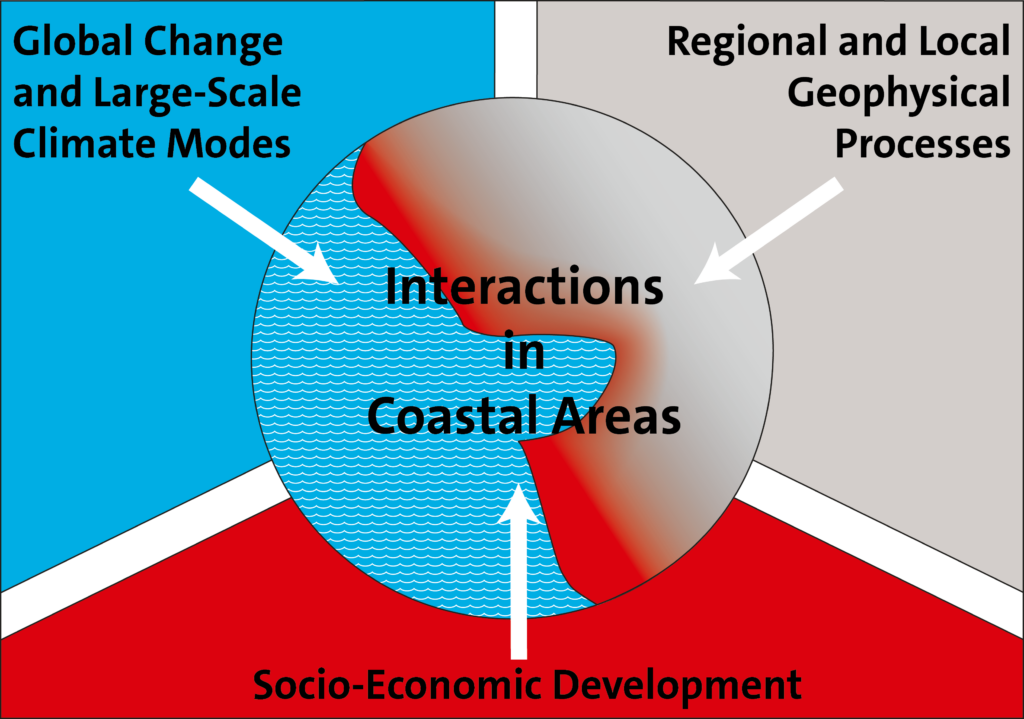

An expanded snippet from an ethnographic journal documented during fieldwork undertaken for the DFG-funded EMERSA project (SPP 1889 Regional Sea Level Change and Society), led by Anna-Katharina Hornidge & Micheal Flitner. My immense thanks to fellow research associate Cora Bolong.

Photo credits: R. Siriwardane ©

Partners

Photo credits: Navotas in Metro Manila, H. Alff ©